Circumstance, Compassion, and Expertise Combine to Save a Child’s Life

Checking in with Owen Coulter three years after his heart stopped at Dell Children’s Medical Center

Reviewed by: Kristin Coulter (patient's mother), Darin Coulter (patient's father), and Amy Greenwood Hemingway, RN, MSN, CNS, CPNP-AC/PC

Written by: Erich Pelletier

On December 13, 2018, 5-year-old Owen Coulter’s heart stopped beating shortly after he arrived at Dell Children’s Medical Center. He underwent 90 minutes of CPR and other critical interventions before his heart began beating again. This now 8-year-old is enjoying a happy life filled with activities any second grader is prone to love, such as riding his bike, fishing, hiking, and building Legos.

“Dell Children’s is not just a medical facility,” shares Owen’s mother, Kristin Coulter. “Dell Children’s is our family because, even post-discharge, they haven’t left our side. We know we can call on them at any time and they’ll be there for us, which is why Owen is doing great.”

“The Incident”

For several days leading up to what Kristin has deemed “The Incident,” Owen had been feeling sick. He complained of pain in his legs, a persistent headache, and fatigue. Concerned he may have picked up the flu or strep throat at school, Kristin and her husband, Darin Coulter, Owen’s father, made an appointment with Owen’s primary care pediatrician.

“Everything came back negative,” explains Kristin. “We were told, ‘Go home. Give him plenty of fluids. This is just one of your typical viruses that will have to work itself out. His body’s just going to have to fight it.’”

Upon returning home, Owen’s symptoms worsened. The following day, Kristin and Darin noticed Owen’s ankles turning purple. They realized the situation may be more serious than a run-of-the-mill viral infection.

Having spent weeks at Dell Children’s the year before with Owen’s older sister, Madelyn, who was diagnosed with Kawasaki disease, a leading cause of acquired heart disease, the Coulters knew what they needed to do next. “There was no doubt in our mind,” shares Kristin. “We were going to Dell Children’s.” They got in the car and headed toward Austin. During the hour-long drive to Dell Children’s from their home in Liberty Hill, Owen became lethargic, his skin turned pale, and he began vomiting. Concerned and frightened, the family stopped at the nearest emergency room. The ER team immediately began checking Owen’s vital signs and realized the situation was even worse than it appeared.

“The ER doctor contacted the Dell Children’s pediatric transport team and insisted on an immediate response at their location,” recalls Darin. While they waited for the transport team to arrive, the ER staff made several unsuccessful attempts to place an IV in Owen’s arm. Upon the transport team’s arrival, the transport nurse was also unsuccessful and had to insert the IV through Owen’s jugular vein.

Kristin rode in the ambulance with Owen while Darin followed close behind. Owen was uncomfortable but alert and coherent as the transport team called ahead to share details of his worsening condition. En route, readings on Owen’s blood gases were obtained and passed along to the team at Dell Children’s. His blood was acidotic, a dangerous condition in which acid levels in the blood are elevated due to a buildup of carbon dioxide brought on by poor lung function or distressed breathing. With this information, the Dell Children’s ER team knew Owen’s situation was critical and began preparations for his arrival.

Upon arrival at Dell Children’s, the Coulters found an ER team prepped and ready for Owen. “We arrived and 15 nurses and doctors were just waiting for us,” says Kristin Coulter. “It was a little overwhelming, I’ll admit, because in my head I’m going from ‘This is just a virus’ to ‘Oh wow, I’m in a trauma room with a whole medical team in an ER at a hospital for children.’”

Hooked up to monitors and IVs with his parents by his bedside in the trauma room, Owen remained alert. He told his mother he was thirsty and needed to go to the bathroom before, suddenly, the line on the electrocardiogram (ECG/EKG) went flat.

“He was in cardiac arrest. His heart stopped,” recalls Kristin. “I remember nurses grabbing my shoulders and pulling me away from his bed and out into the hall. Darin stayed by his bedside as the team lined up and started CPR within seconds.”

CPR continued for over an hour with teams of five providers rotating every two minutes. When a team member got tired, a new provider rotated into the queue. Doses of epinephrine (a form of adrenaline) were pushed through the IV placed in Owen’s jugular vein by the emergency transport team in efforts to prompt his heart to beat again. Though his heart was revived several times during this process, those moments were brief.

A veteran firefighter who had worked with patients in cardiac arrest, Darin understood the importance of calm mental and emotional support in emergency situations. “I knew I had to stay there. I held his hand the whole time, telling him to keep fighting and hang on,” shares Darin. Several of the nurses expressed the impact of having Darin in the room while they continued to perform CPR. “I was told, ‘I remember staring at you the whole time. You were calm and by Owen’s side, talking to him, and that’s what kept us going.’”

In another area of Dell Children’s Medical Center, a pediatric cardiac surgery team was preparing for a scheduled procedure on a patient of their own. Just six months prior to Owen’s arrival in the ER, Charles Fraser, Jr., MD, was recruited to join Dell Children’s as the Chief of Pediatric and Congenital Heart Surgery. Dr. Fraser, who has been part of some of the finest institutions in medicine, developed and continues to lead the Texas Center for Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease, a clinical partnership between Dell Children’s Medical Center and UT Health Austin.

An extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) machine was on standby in case it was needed during the cardiac surgery team’s procedure. ECMO is a cardiac bypass technology in which a patient’s body is oxygenated without their blood needing to pass through the lungs or heart. Blood is pumped through a tube connected to a major artery in the patient’s neck, chest, or groin into an artificial lung and then back into the body. ECMO can provide prolonged life support during procedures when a patient’s heart needs to be stopped, but it is rarely used in emergency room situations and had never before been used in an emergency at Dell Children’s.

Kristin relays the conversation she had then with the team, stating, “They told us, ‘We have a hail Mary situation here. We’ve never done this before, but if you’re willing to let us, we want to try it.’” As it turned out, the cardiac surgery team’s patient did not need the ECMO machine that day. “So, the entire ECMO team came from the surgery area to the ER,” continues Kristin, “and they turned that emergency trauma room into an operating room while still administering CPR.” The quick thinking and expertise of the cardiac surgery team, along with the presence of the ECMO machine, likely saved Owen’s life.

“Everyone took a risk in that moment. That team took a risk,” continues Kristin. “That team had faith in one another and knowing they had no other options, said ‘We’re going to go for it.’” The risk paid off. After 90 minutes of CPR, Owen’s heartbeat returned and, this time, remained.

“He’s got the big ECMO scar,” says Kristin. “It’s a gnarly scar. We tell him it’s his ‘warrior scar.’”

Recovery and the Long Return to Health

Regaining his heartbeat was just the beginning of a long road back to health for Owen. In the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU), Owen stayed connected to the ECMO machine and a dialysis machine while his breathing was supported by a respirator. “There were five days where he fought for his life,” remembers Kristin. “He went into kidney failure. He had multiple strokes. He had blood pools in his brain. It seemed like everything that could go wrong went wrong.”

But Owen held on, making incremental improvements with each passing day. After five days, his heart and blood oxygen levels fared well enough that the ECMO machine could be turned off. Later, he came off dialysis. On Christmas Eve, three weeks after “The Incident,” Owen was removed from the ventilator and allowed to wake up. “That was the moment when the whole team wondered if he would recognize me and Darin due to the brain damage we feared may have been caused,” says Kristin. “The first thing he said was, ‘Where’s mama?’ The whole unit was clapping and cheering.”

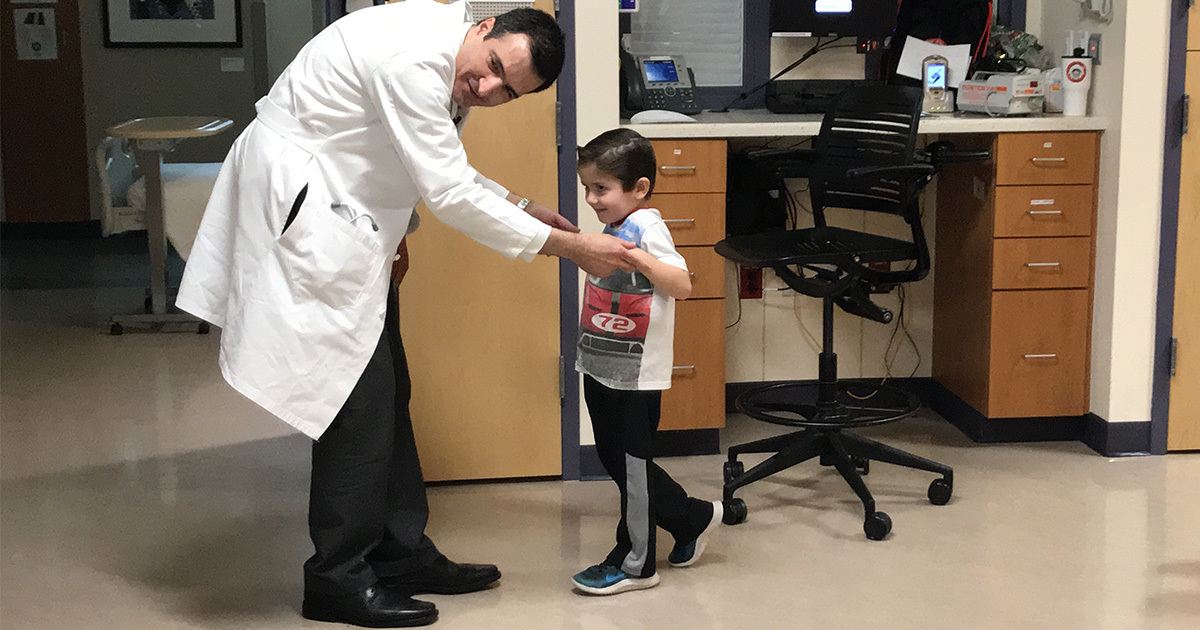

After a month in the PICU, Owen was moved to the rehabilitation unit where his body and mind were retrained for normal functioning. “He had to learn everything again,” explains Kristin. “He had to learn how to eat and talk and crawl and walk. We sort of went back to the infant stage.” With 30 days of rehab under his belt, two months following his cardiac arrest, Owen was discharged from Dell Children’s to return home with his family. With the assistance of a walker, Owen was able to walk a few steps on his way out of the hospital.

A Path Back to Normalcy, but Surrounded by Mystery

Today, Owen is a vibrant, curious second grader. “He’s in a mainstream classroom with his twin brother, Hudson. He’s receiving special services in school, but he’s progressing at his own rate, which is just fine with us. And, wow, he’s got a personality.” says Kristin. “We noticed a personality change after “The Incident.” We’ve learned that’s normal, too, with strokes, and he just kind of landed on the goofy side of the personality spectrum.”

But mysteries remain. Owen was diagnosed with myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart muscle (myocardium) that can lead to cardiac arrhythmias (irregular heart rhythms) and reduce the heart’s capacity to pump. Myocarditis is usually caused by viral infections, though reactions to pharmaceuticals can also be a factor. If myocarditis is severe, it can drastically reduce the ability of the heart to provide sufficient oxygenated blood to the body, which often result in strokes and heart attacks.

Owen’s case, however, is different. After hundreds of tests were sent for assessment to multiple labs across the country, no conclusive indication of viral infection was found. “Owen has a story that’s kind of a black box right now,” explains Kristin. “There are still a lot of unknowns.”

Though Owen received genetic screening during his stay at Dell Children’s, the Coulters had further testing done in early 2020 to determine whether there is a genetic component to his condition. Screenings detected that Owen carries a reasonably rare mutation in the desmoglein-2 gene (DSG2). DSG2 mutations are associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC), a condition in which the heart muscle atrophies progressively.

“The crazy thing is that there are no other records in the national genetic database of anyone under the age of 40 or 45 having this mutation,” shares Kristin. “Owen is the only one.”

Though it is not 100% certain that Owen’s DSG2 mutation led to his cardiac arrest, his parents and care team believe the correlation could be strong. They had the rest of the family undergo testing to determine whether his parents or siblings also carry the mutated gene. Those tests determined that Darin and Owen’s twin brother, Hudson, are also carriers. As a result, Darin, Hudson, and Owen now undergo annual cardiology screenings to monitor for potential concerns.

Continuing Collaborative “Whole-Person” Care

For the first year following “The Incident,” Owen received intensive, ongoing therapy across a range of specialties and disciplines at Dell Children’s. “We basically lived at the Dell Children’s outpatient center in Cedar Park, where Owen had physical therapy and occupational therapy multiple times a week,” says Kristin. “He went in not being able to walk and now has what we call his ‘Owen Run.’”

The damage done to Owen’s kidneys continues to be monitored by nephrologists, and he will likely continue to undergo routine checkups for many years. As there is very little research surrounding the impact of ECMO cardiac bypass procedures on pediatric patients, Owen also continues to receive annual checkups in other areas, including his vision and hearing

Neurologically speaking, Owen suffered traumatic brain injury due to the strokes he experienced, so he receives routine neurological testing to chart his progress. “They’re now realizing, because his lower spine and core are still very weak, that there was potentially a stroke in his lower spine,” explains Kristin. Owen also receives support from Dell Children’s neuropsychology teams.

“He’s a happy dude. He loves life,” says Kristin. “As an 8-year-old, kids can be mean. We’ve needed to really coach him on how to share his story in his own words because people ask why he can’t run and keep up with his peers.”

Kristin reflects on the care and support the family has received from Dell Children’s Medical Center, stating, “The fact that we don’t have to worry about trying to get to other hospitals in big cities for Owen’s care, the fact that the city is growing to the point that we have the technology and the expertise and we’re recruiting top physicians, that’s a real peace of mind.”

“We’re still healing,” continues Kristin, “but it’s a very positive healing journey that we’re going through. We know there may be a point in the future when we have to intervene, again, for Owen, but we find some relief in knowing the whole Dell Children’s team is with us.”

For more information about the Texas Center for Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease, click here.